Viruses and other parasites are famously adept at trickery and manipulation. Think of your favorite creepy example of that, then consider a new paper about a virus so devious that it might become your new favorite (if you’re into that sort of thing). The article in Science Advances reveals the strategic brilliance of the tomato yellow leaf curl virus (TYLCV), which infects tomato plants with the help of its vector, a whitefly. Step 1 of the evil plan: the virus induces the plant to make a protein that attracts the whitefly. Nice move, but now there’s a new problem, which is that flies are attracted to already-infected plants. Our scheming virus wants the flies to carry it to uninfected plants. So, step 2: the virus inhibits the fly’s olfactory receptor that makes it home in on that attractive signal. At first this might seem like the virus is undoing its work, but think about it: now only uninfected flies will be attracted to the infected plants. That means more infected flies, which now no longer prefer the infected plants! [virus voice] MWAAAHAHAHAHA.

Here the authors nicely summarize the evil plan, using vivid language that highlights the strategic brilliance of this devastating pathogen:

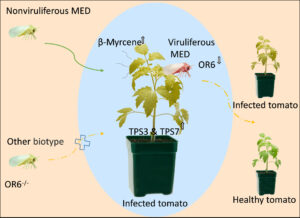

These results reveal a unique two-tiered pull-push strategy in which TYLCV maximizes transmission by modulating terpene release from host plants as well as the olfactory system of its vector.

A plant virus manipulates both its host plant and the insect that facilitates its transmission

In Science Advances, 28 February 2025

From the groups of Ted Turlings, Wen Xie, and Youjun Zhang.

Snippet by Stephen Matheson

Image credit: Figure 6 from Liang et al. linked above (CC-BY-NC-ND).

In Defense of TYLCV: What is Free Will?

You call it manipulation. I call it life.

Whiteflies are always responding—to light, temperature, plant volatiles, hormones. Their choices aren’t really choices at all, just gene expression shifting in response to the world around them.

So now, TYLCV comes along, tweaking olfactory receptors, nudging flies away from infected plants, urging them to spread its genetic material. But is this really so different from any other stimulus?

Plants manipulate whiteflies too—releasing volatiles to lure them in, changing their chemistry to shape insect behavior. The environment pulls the strings—cold slows their flight, drought-stressed plants drive them away.

Tell me: who isn’t being controlled? If not the virus, then something else would be dictating their path.

Maybe TYLCV isn’t an invader, just another environmental force shaping whitefly destiny—no different than a shifting season or a host plant defending itself. Maybe whiteflies don’t “choose” to move; they simply follow the biochemical currents that have always dictated their existence.

So if they spread this virus, is it manipulation? Or is it just nature?

They go where their olfactory receptors tell them. And right now, those receptors are telling them: leave this plant and find another.

(Written in collaboration with ChatGPT 😉 )

All well said! I still love creating melodramatic narratives of “invaders” with “evil plans,” especially if I can invoke a virus’ evil laugh. And I totally agree that the plants are gleefully manipulating the flies; plants are master manipulators, probably since they are awkwardly anchored to the earth. But in defense of the concept of “manipulation,” I will point to Richard Dawkins’ best book, not The Selfish Gene (which is great) but The Extended Phenotype (its sequel). See especially the chapter “Arms Races and Manipulation” with a great paragraph on page 67 (https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Extended_Phenotype/EDViIysU0uEC?hl=en&gbpv=1&pg=PA67&printsec=frontcover)

Damn, Stephen! I’m ashamed to admit that I haven’t even read The Selfish Gene (please don’t revoke my PhD). When thinking about TYLCV and pathogens in general, it also makes me think about all sorts of relationships – different kinds of symbiosis – (“AI overview” – Symbiotic relationships are close interactions between different species, and the main types are mutualism (both benefit), commensalism (one benefits, the other is unaffected), and parasitism (one benefits, the other is harmed). ). Of course I love the anthropomorphizing of TYLCV, but then it would lead me to do the same for rhizobia (so kind) vs Ralstonia solanacearum (what a jerk) – but neither really had any choice in the matter. And then it leads me to who’s manipulating whom, really, and is it manipulation or just a program we’re all relatively hard-wired with. I mean, this is not at all to say that TYLCV is tolerable, particularly if you love tomatoes, but I mean, I admire their evolutionarily successful strategy. #survivalofthefittest

(nor have I read The Extended Phenotype).