Have you heard about the Iberian ribbed newt? This creature could be a vision from the Locked Tomb series by Tamsyn Muir. It’s goth, it’s metal, it’s… well look, if you are foolish enough to piss this animal off, it will stab you with its own ribs, which it brandishes through its skin and which gather poison on the way out. You will learn your lesson, and the newt will go on with her/his day, because it is also famous for its regenerative capacities.

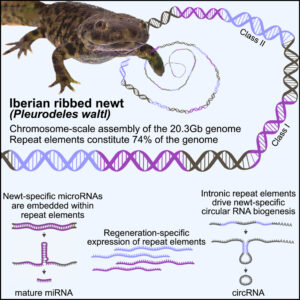

The authors of a new paper in Cell Genomics undertook the epic quest to assemble the complete gigantic genome of this adorable nightmare. (Apparently the newt is more welcoming to genomic parasites than it is to human handlers.) The scientists seem more interested in regeneration than in gothic horrors, and they show that some of the newt’s vast hordes of genomic parasites (transposable elements) are likely involved in regeneration. The hordes are indeed vast: 3/4 of this animal’s giant genome is made of transposable elements. Here is their final paragraph, which nicely expands our vision beyond the newt and its gothness:

From a broader perspective, the data uncover how repeat elements shape a gigantic genome, serving as common denominators between genome expansion, facilitation of circRNA formation, and evolution of miRNAs from stem-loop structures. Furthermore, the chromosome-scale assembly of P. waltl provides a useful resource that facilitates our understanding of vertebrate chromosome evolution, not the least, variations among syntenic blocks and gene content. Our results thus allow for the exploration of species-specific innovations and evolutionarily shared molecular responses to major injuries, knowledge necessary to identify mechanisms that promote or counteract successful regeneration.

Chromosome-scale genome assembly reveals how repeat elements shape non-coding RNA landscapes active during newt limb regeneration

In Cell Genomics, 12 February 2025

From the labs of Nicholas D. Leigh, Maximina H. Yun, and András Simon.

Snippet by Stephen Matheson

Image credit: graphical abstract from Brown et al. linked above (CC-BY)